|

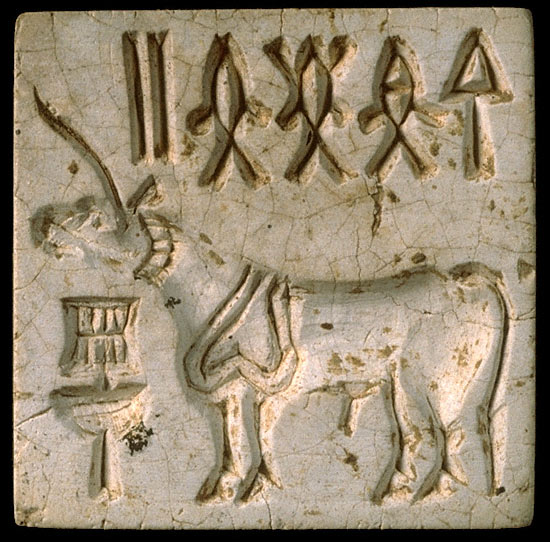

| Unicorn seal from Harappa, c. 2200 BC. Image: Harappa.com. |

This project explores the history of medieval information technology by modelling writing as code. But what, exactly, does writing encode? Answers to this question are complex, significant, and richly productive.

what does writing encode?

The easy answer is that writing encodes information. The earliest forms of writing seem to have been used for accounting. However, there is some debate among historians of writing over whether visual semiotic systems that encode non-linguistic information should be considered ‘writing’. This is perhaps a semantic quibble, but it underlines a very important historical development: at some point, every writing system commonly used today was adapted for linguistic information. Since the most commonly and frequently used method that humans use to create, store, transmit, and process information is verbal – that is, humanly usable information is mostly linguistic – this tight linkage of writing and language became overwhelmingly powerful. It is easy to think of writing only as a representation of language, and of spoken language in particular.