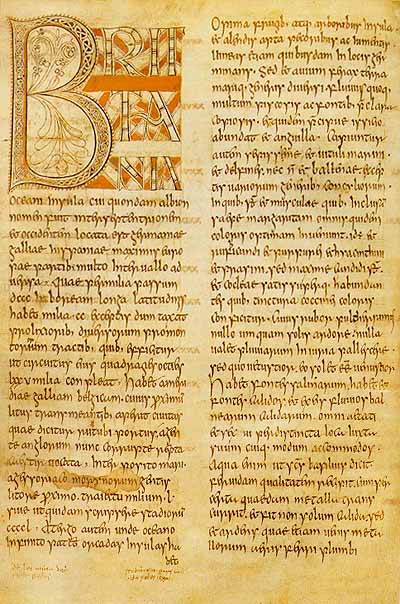

While looking for early English examples of omission signs and symbols called signes-de-renvoi, I came across the "St. Petersburg Bede", or "Leningrad Bede," one of the oldest manuscripts of Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum. In the facsimile copy at the University of Saskatchewan, there are only five visible annotations in the whole manuscript (f.11v, 21v, 68r, 89r, 90v), despite many more inline marks that would suggest a corresponding marginal note or correction. After checking bibliographic records, it appears the manuscript was trimmed at some point in its life!

For most people studying Bede, I’m sure these annotations are not missed much in such a clean and exemplary text for its age, which contains the oldest known example of a historiated initial. But for someone looking for annotations, it is an unfortunate loss. The decision to trim the pages was likely for usability, as well as an aesthetic choice. Turning the pages is harder when they are not even, and the book’s opening is cleaner when it is uniform.

Since I am working an article on the symbols used to guide the reader to annotations in the margin and swiftly back again, I will not overdramatize the fact that some of these are missing from one of the oldest examples of Old English text we have. But I cannot help thinking about the practice of trimming manuscripts within our own context in the world of digital humanities, and this serves as an example of the type of information the Medieval Codes project endeavors to find in early English manuscript and print. The goal of digital texts is to transpose text from one medium (manuscript) to another (digital text and code). In this process, we have many usability and aesthetic choices to make. It’s true, we don’t trim pages, and we even ensure that they are photographed in their entirety, but we make concessions in other ways. Due to space constraints and load times, archival images are usually restricted to somewhere between 300 and 1000 dpi, depending on the size of the document. This is fine for one type of reading of the text, for accessing some forms of information, recognizing the words. On the other hand, looking at particular words, marks, and symbols or decoration, is not always easy. This is not to disparage archival practice, and it is not a plea for the necessity and primacy of the manuscript page, but a comment on the difficulty of reconciling usability, aesthetic choices, and financial considerations, with the importance of conserving archival material.

Since I am working an article on the symbols used to guide the reader to annotations in the margin and swiftly back again, I will not overdramatize the fact that some of these are missing from one of the oldest examples of Old English text we have. But I cannot help thinking about the practice of trimming manuscripts within our own context in the world of digital humanities, and this serves as an example of the type of information the Medieval Codes project endeavors to find in early English manuscript and print. The goal of digital texts is to transpose text from one medium (manuscript) to another (digital text and code). In this process, we have many usability and aesthetic choices to make. It’s true, we don’t trim pages, and we even ensure that they are photographed in their entirety, but we make concessions in other ways. Due to space constraints and load times, archival images are usually restricted to somewhere between 300 and 1000 dpi, depending on the size of the document. This is fine for one type of reading of the text, for accessing some forms of information, recognizing the words. On the other hand, looking at particular words, marks, and symbols or decoration, is not always easy. This is not to disparage archival practice, and it is not a plea for the necessity and primacy of the manuscript page, but a comment on the difficulty of reconciling usability, aesthetic choices, and financial considerations, with the importance of conserving archival material.

Many important aspects of a text are outside of the “linguistic dimension,” to use Jerome McGann’s terminology from The Textual Condition. Some of the “bibliographic codes” are encoded in the text’s organization and get lost when marginal content is disregarded or physically removed. There are tactile and extra-visual features of manuscript, social functions and psychological processes which are important to understanding manuscripts and printed books as well. While archival images and digital text encoded and displayed on a computer may not be able to capture all of the information in manuscripts, it is important that we study these extra-textual features.

Ben Neudorf

"we are mining a technology with a long history of human interaction for tools that our ancestors found effective for accessing information"This may bring up questions of how to digitally encode signes-de-renvoi, which are both idiosyncratic and based on convention, or whether a page turned or made into a tab for easy access can adequately translate to a link or bookmark in a digital text. More importantly, by paying attention to how medieval texts are organized, we are mining a technology with a long history of human interaction for tools that our ancestors found effective for accessing information, keeping in mind that speed and effectiveness are not necessarily related. Computers were built with calculation in mind, but books were created to facilitate human navigation of text. We have a lot to learn from books that can only enrich our digital experience with text. Part of the process is looking outside of the purely textual, and into the social, psychological, and bibliographical aspects of our navigation of books.

Ben Neudorf

No comments :

Post a Comment